Manufacturing Carbonated Water

Although

bottle filling machinery and bottle stoppers evolved considerably during

the second half of the nineteenth century, the process of manufacturing

carbonated water changed very little.

Two methods of carbonated water production evolved, known as the

“English Continuous System,” and the “Standard American System.”

The basic difference between these two approaches was the way in

which the water was carbonated.

The English system enabled bottlers to fill bottles indefinitely,

stopping only to recharge the acid and marble dust in the generator.

Water was drawn continuously into the generator with only

occasional adjustments to pressure valves.

The American system required refilling of the water cylinders

when they were empty. If a

cylinder was dry, water couldn’t be added without wasting the remaining

carbon dioxide it contained.

Although the American system required additional maintenance, it

was the predominant approach used by

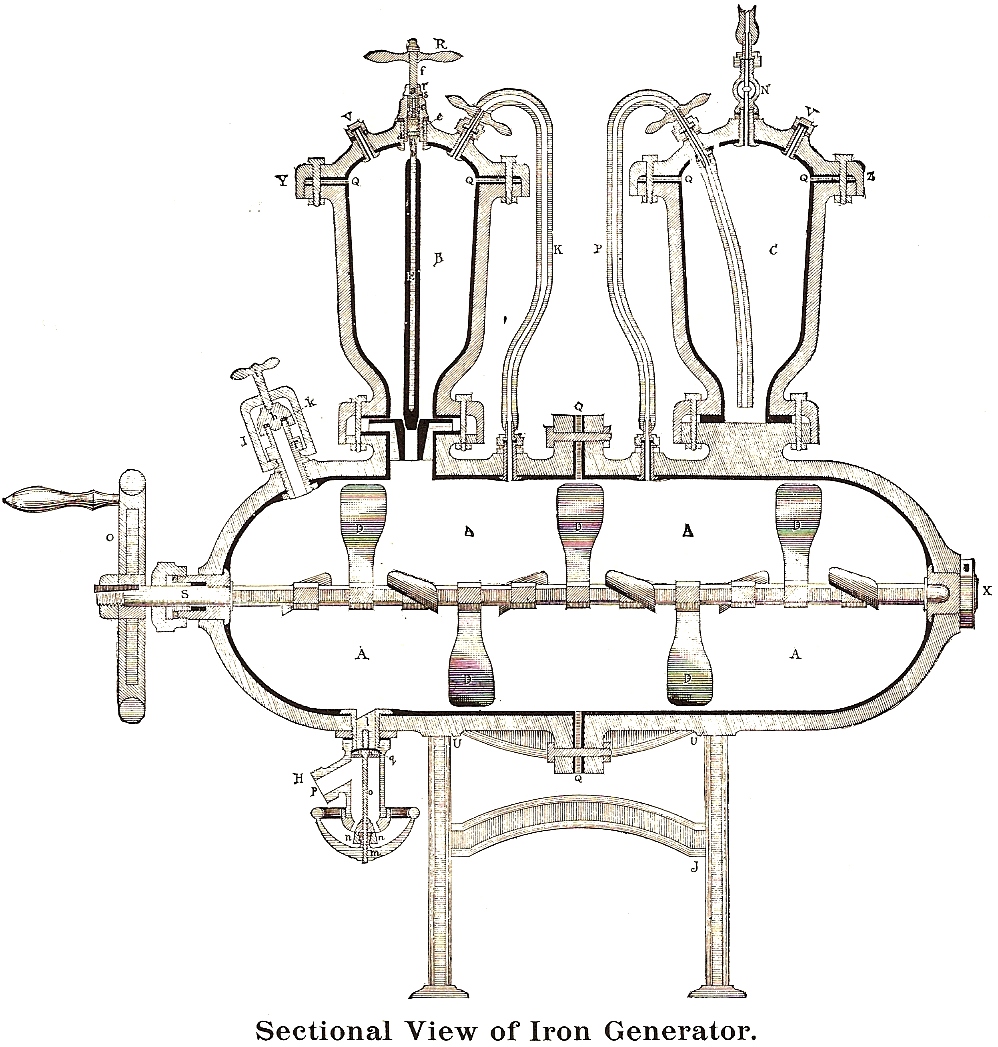

In order to bottle with the

American system, the cylinder was filled three-fourths full of water.

Then several pounds of marble dust (calcium carbonate) and

bicarbonate of soda (to keep the marble dust dissolved evenly, soften

the mass, give it a smooth, lump-free texture, and cause the gas to be

more freely generated) were introduced into the marble chamber, along

with enough water to aid in agitation of the mass.

Next, a quantity of sulfuric acid was poured into the acid

chamber and then released into the marble chamber by means of the acid

valve. As the agitator

wheel was turned slowly, the gas was released from the marble dust and

flowed thru the gas pipe and into the cylinder.

This gas dissolved in the water producing carbonated water.

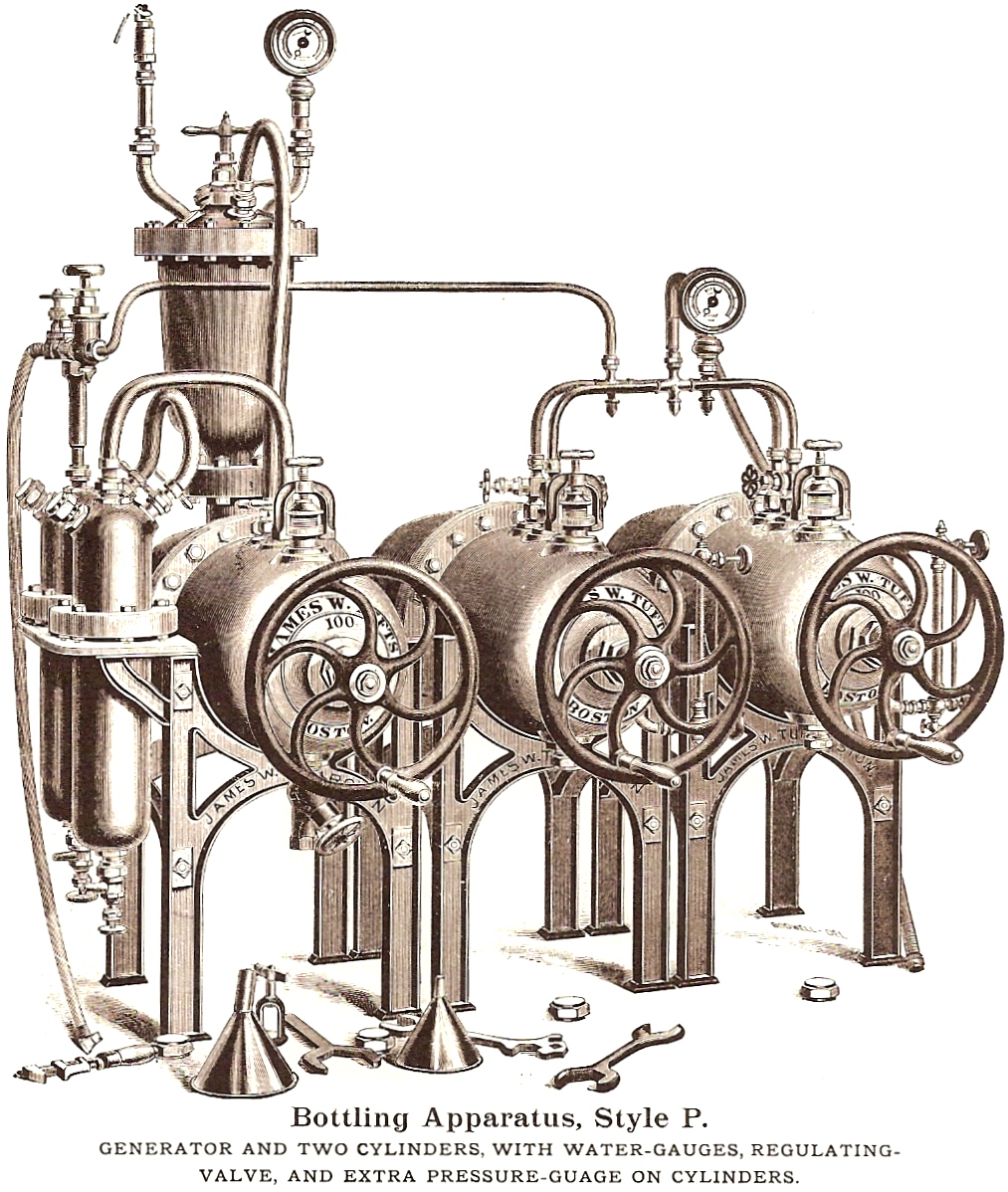

James W. Tufts’ 1888 book,

The Manufacturing and

Bottling of Carbonated Beverages,

listed “Marble-Dust. Price

per barrel, delivered free on board in

As the gas supply decreased, more acid could be let

into the marble chamber to react with any remaining marble dust.

Once the water in the cylinder was charged to the desired

pressure, the discharge valve was opened and the carbonated water

allowed to flow thru a hose to the bottling table.

Due to the corrosive nature of sulfuric acid, generators were

always rinsed thoroughly with fresh water.

Generators were typically six to seven feet tall and

weighed 1,000 pounds, with larger ones weighing as much as four tons.

They were easily kept in working order, but when damaged often

required shipment to the manufacturer for repairs.

Most damage involved collapse of the block tin or lead lining due

to a sudden reduction in pressure.

Foreign objects in the marble dust also tore the lining or bent

agitator blades. The

greatest operating danger posed by generators typically occurred when

the wrong valve was accidentally opened or closed, causing the internal

pressure to rise, exploding the generator and spraying the acidic

contents.

The safe and successful operation of carbonated water

generators required a thorough understanding of how this sophisticated

machinery functioned. For

those seeking additional details, James W. Tufts’ 1888 book,

The Manufacture and

Bottling of Carbonated Beverages,

provides highly detailed descriptions and operating instructions for

setups of one generator with one, two, or three cylinders, and several

other configurations. The

accompanying illustrations show a typical installation (note the tools)

and a sectional view revealing the inner workings of the cylinder, and

acid-chamber, and a purifier.

Tufts produced cylinders of both iron and copper, with both

styles having block tin linings.

HutchBook.com

HutchBook.com