Syrups

Simple syrup was made by

dissolving granulated sugar in filtered water in order to produce a

basic, thick sugar solution.

Syrups were produced by either hot or cold processes.

Hot process syrup was made by dissolving sugar at a

ratio of 50 pounds of granulated sugar to 4.5 gallons of warm, filtered

water. The mixture was

heated very slowly and never boiled.

Perfectly clean, twenty to forty gallon, tin-lined copper tanks

were used to mix and contain the syrup.

A spigot at the base of the tank was used to draw off the

contents after mixing and the syrup’s strength was measured with a

hydrometer. The syrup was

strained or filtered thru felt, flannel, or silk before it cooled, and

again before use. Most

bottlers made their own syrups, but purchased their extracts.

Fresh fruits were often mashed and mixed with the syrup for

flavoring, but this type of syrup was highly perishable and could only

be used on the day it was made.

Cold process syrup was made by dissolving granulated

sugar in cold, filtered water by stirring the mixture.

Cold process syrup wasn’t as desirable as hot process syrup

because undissolved sugar often crystallized and clogged the syrup gauge

valves.

James W. Tufts provided strong guidance on “The

Manufacture of Syrups” in his 1888 book,

The Manufacture and

Bottling of Carbonated Beverages,

including:

The most important point to be observed in the

manufacture of syrups is scrupulous cleanliness.

This point cannot be too strongly insisted on, as upon it depends

the ultimate success of many manipulations.

Even the smallest bottling establishment should have a

place set apart as a laboratory.

Both the quality and cost of various beverages depends upon the

care and accuracy with which the various ingredients are compounded.

In order to have a uniform and even quality of goods,

it is necessary to have proper measures, filters, tubs, etc.

If a spoon is used for a graduate, an old sieve for a filter, and

the household wash-tubs and boiler instead of tanks and kettles

specially provided, the goods cannot fail to be of poor quality…The cost

of the necessary articles is not great, and with care they will last for

years…

The laboratory should be supplied with a jacket-kettle

or similar contrivance for making simple syrup.

It is not safe to use dry heat in preparing syrup, as it is

easily burned…

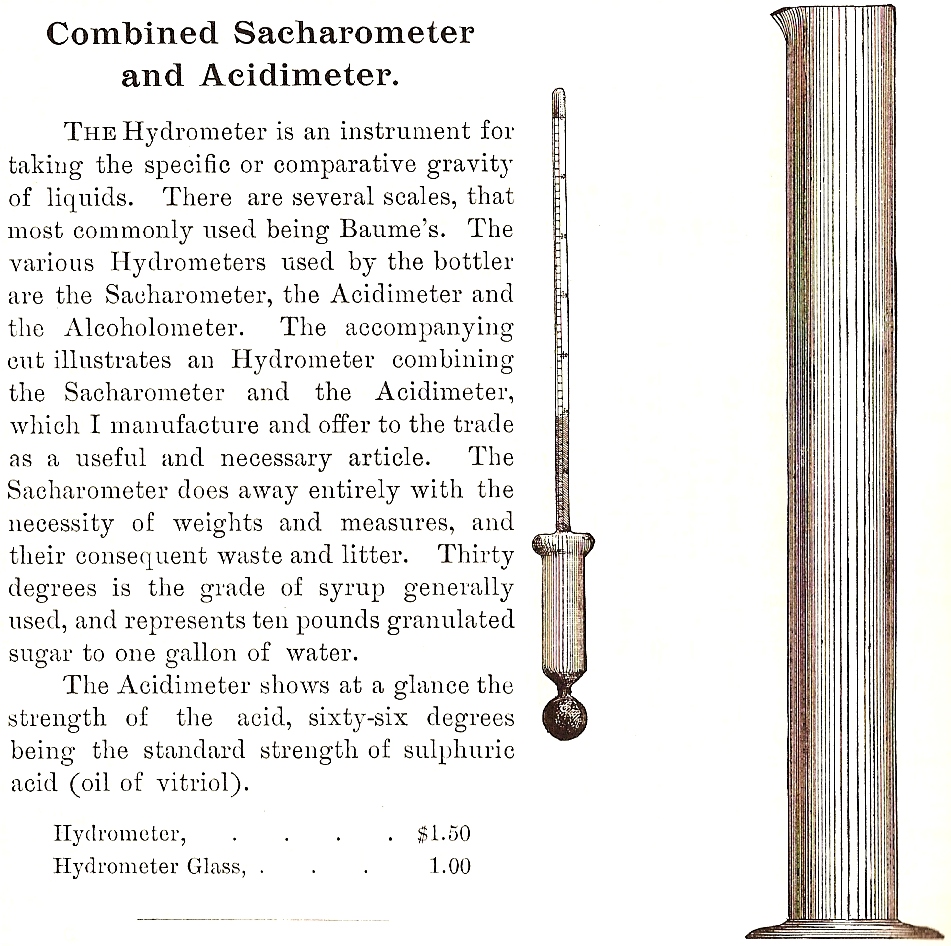

The hydrometer, a closed glass tube, graduated and

weighted at the end, for determining the density of liquids, is a

necessary instrument in the laboratory.

The various hydrometers used by the bottler, are the

alcoholometer, for liquid lighter than water, and the sacharometer and

acidimeter for liquids heavier than water…

A graduate glass for fluid measures should also be

supplied. These articles

enable the bottler to dispense with the use of scales for weighing,

which require so much care to keep clean, besides saving time and labor

in handling.

Filtering paper, large-mouthed bottles for salts and

extracts, and earthen jars for holding syrups, are also necessary

adjuncts of the laboratory…

A wooden spoon or stick should be used in stirring

syrup which contains acid…

To make Syrup Brilliant…(and) produce a perfectly

transparent beverage for use of bottlers and others, it is simply

necessary to…Mix one ounce of powdered carbonate of Magnesia with each

gallon of flavored syrup, and filter through fine flannel.

A little of the first run should be filtered a second time until

it runs clear. The improved

appearance of the beverage makes the process a most desirable one…

No inflexible rule can be given for the use of color.

Always color to suit, and use care not to get too high a color.

Acid and color should not be added to syrup one immediately after

the other. Add the

flavoring or foaming extract between the two.

Use good extracts.

There is nothing in which more deception can be practiced.

Always purchase extracts

from thoroughly reliable

houses.

Here are two examples of Tufts’ typical syrup

formulas:

Strawberry

Syrup.

Simple Syrup = 1 gallon

Tufts’ Strawberry Extract = 1 ounce

Fruit Acid = 1 ounce

Soda-Foam = 2 ounces

Fruit Color = 2 ounces

Cream Soda.

Simple Syrup = 1 gallon

Tufts’ Cream Soda Extract = 2 ounces

Tartaric Acid = 1 ounce

Soda-Foam = 1 ounce

Tufts also provided mixing and storage advice for

Soda-Foam, Fruit Acid, and Tartaric Acid, helping to better understand

the usage of these frequently added ingredients:

Soda-Foam.

Tufts’ Dry Soda-Foam (one package) = 4

ounces

Alcohol = 4 ounces

Water = sufficient

Place the Dry Soda-Foam in a pint bottle and fill with

water; place the bottle in hot water for several hours; when cold,

strain through cloth and allow to settle until it becomes clear.

Decant; add the alcohol and enough water to make it measure 1 ½

pints. This will never

spoil. Be careful not to

use enough to taste. Never

add foam to syrup until about to use it.

Fruit Acid.

Citric Acid = 4 ounces

Boiling Water = 8 ounces

Dissolve thoroughly and strain through a flannel

cloth. Keep this acid

solution in a glass or stone bottle or jug, well corked.

Prepare in small quantities, as it will become musty if kept too

long.

Tartaric Acid

Solution.

Tartaric Acid = 3 ounces

Hot Water = 8 ounces

Dissolve the acid in the hot water and filter through

paper. Never keep much of

this solution in stock, as dissolved tartaric acid is a very unstable

article, and apt to deteriorate on short notice.

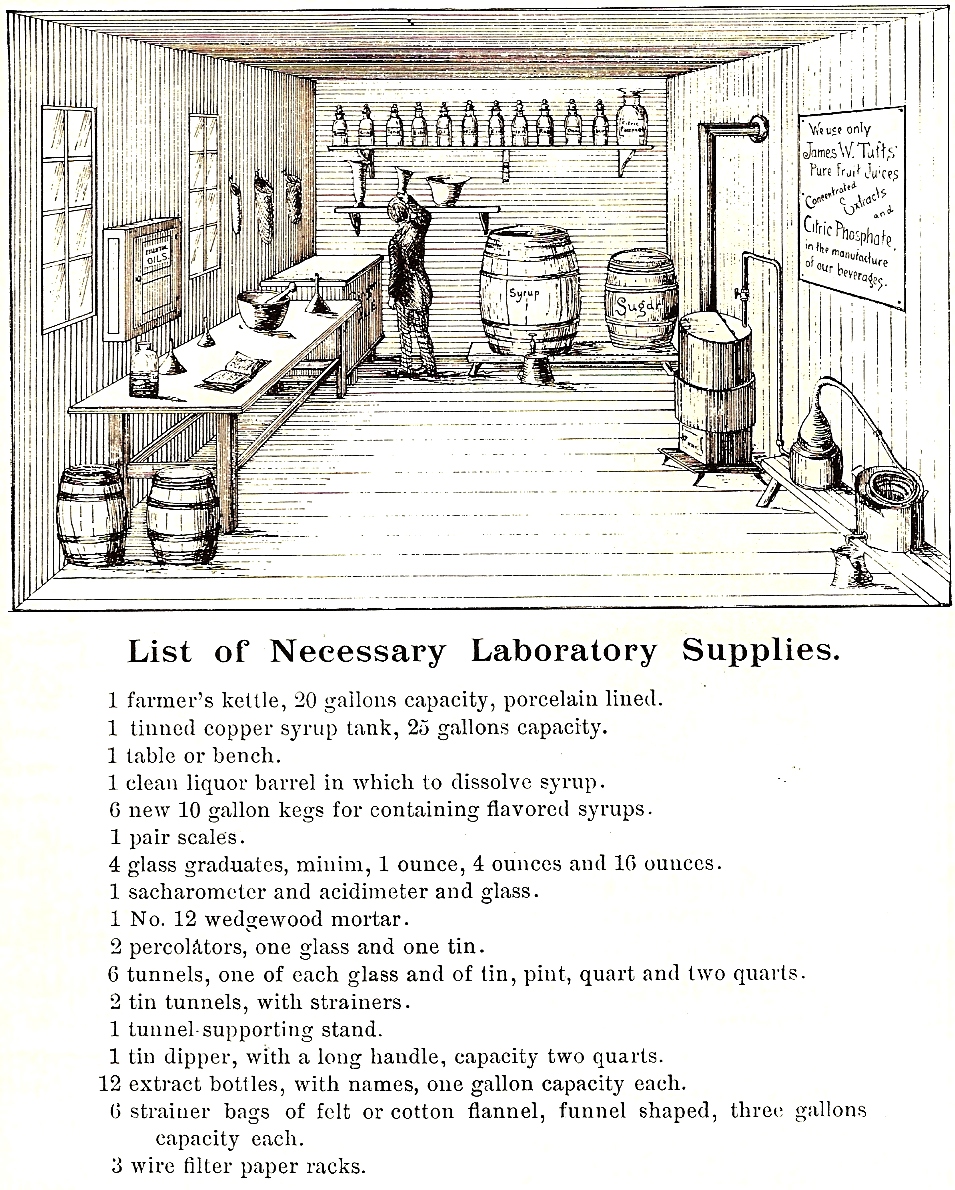

The following illustration and list of suggested lab

supplies accompanied Tufts’ discourse on syrups:

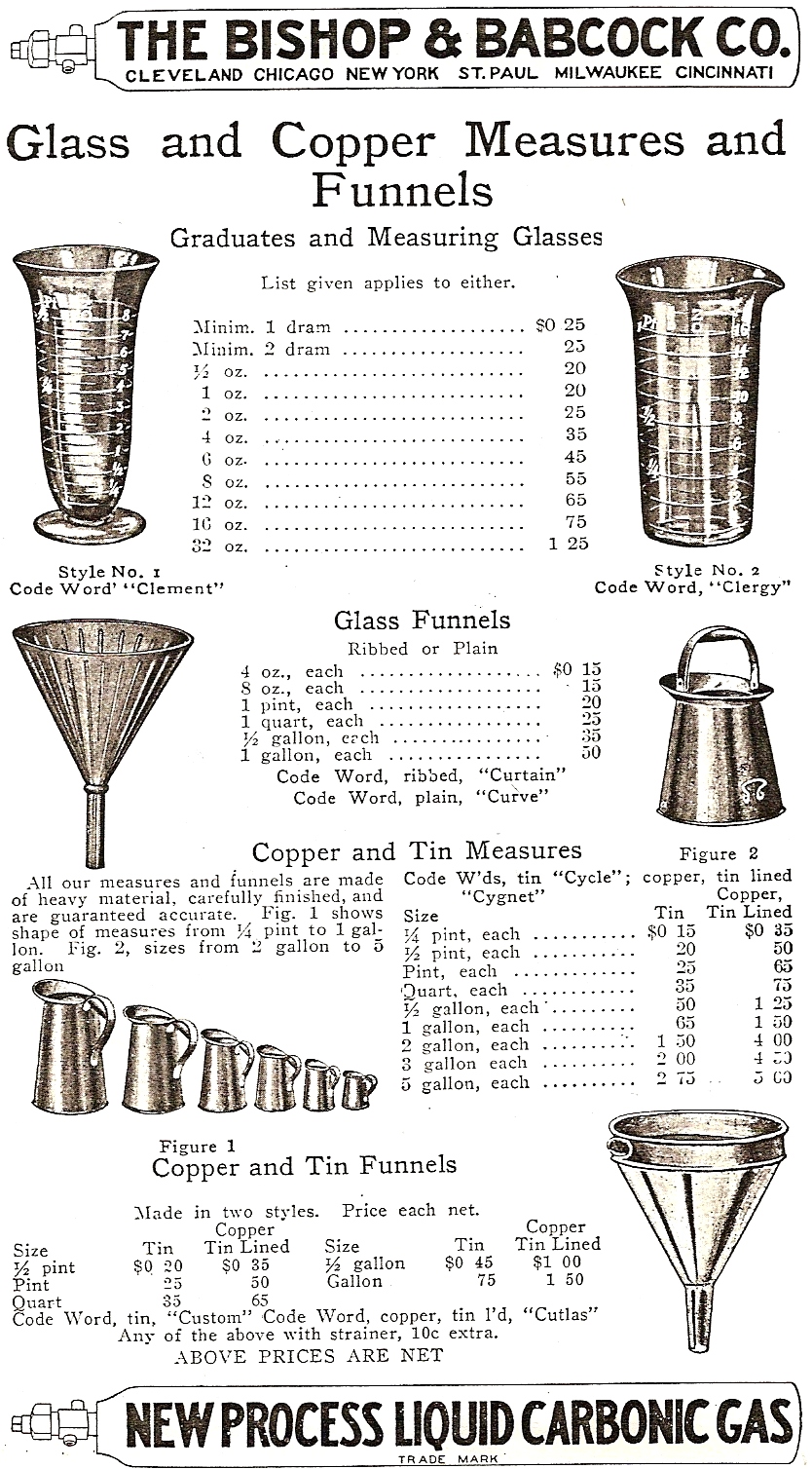

The following page of measures

and funnels offered for sale in Bishop & Babcock’s 1909

Bottler’s Machinery –

Bottler’s Supplies catalog illustrates the typical variety

of laboratory supplies utilized by many bottlers:

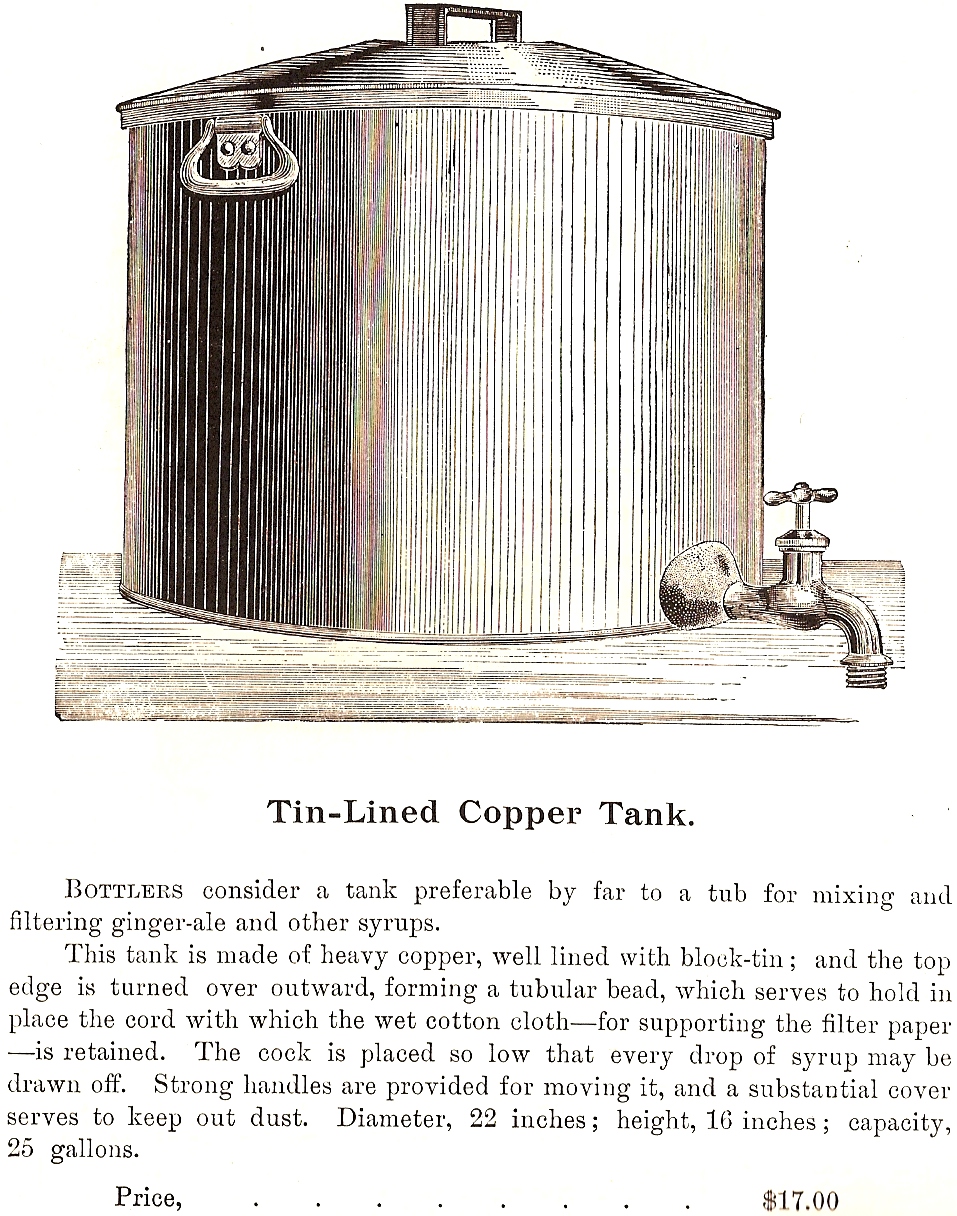

Here’s an advertisement for a

syrup tank (also referred to as a “syrup can”) that James W. Tufts was

selling in 1888:

Charles

Sulz included the identical syrup can illustration in his 1888 book

A Treatise on Beverages or

The Complete Practical Bottler and cautioned:

Syrup Receptacles…are the necessary conjunctions of

the bottling machine with syruping arrangement.

They contain the ready-made and previously flavored syrup which

feeds the syrup gauge or syrup pump, and is intended for flavoring

carbonated water. It is

necessary or at least advisable, where different beverages by a

continuous bottling process are being produced, to have for each kind of

flavored syrup a separate syrup can or tank, which can be quickly and

without delay connected with the syrup gauge and bottling machine…

It is highly important to avoid any exposure of

flavored syrups to copper, lead or zinc, as its chemical action on such

metals results in a contamination which not only destroys its beneficial

effects, but renders it positively noxious.

Ordinary tin vessels should be banished from the bottling

establishment. Galvanized

iron tanks are unfit for syrup receptacles, as the syrup would be

contaminated by the zinc, which is the coating of such tanks.

To secure perfect purity it is necessary to use syrup tanks lined

with good block or sheet tin, thus making any contact of the syrup with

injurious metal absolutely impossible.

Porcelain-lined syrup tanks or slate tanks or glass

vessels are the best, as even tin will be gradually attacked by the

syrup and the citric and tartaric acids it contains…No metal faucets

should be attached to syrup receptacles; faucets of glass or porcelain

are the best.

Glazed earthenware vessels should not be used, since

it is known that into their finish chemical compounds, lead, etc.,

enter, which injuriously affect the syrups and even destroy their

flavors.

Tufts also supplied this combined sacharometer and

acidimeter:

Flavorings were added to the syrup before use.

The 1910 W. H.

Hutchinson and Son Bottlers’ Supplies

catalog recommended:

When flavoring syrup, put in one ingredient at a time

and mix thoroughly before adding another, using a wooden spatula or

stick to stir. Never use

metal. Use only the best

flavors and coloring, and beware of cheap dealers and fraudulent goods.

Do not confound quality with strength.

The essential qualities of bottlers’ flavors are delicate

fruitiness of flavor, rich aroma and solubility.

Too great concentration impairs these qualities and injures the

bright, clear, sparkling appearance of the beverages…Coloring should be

used very carefully. Avoid

high colors.

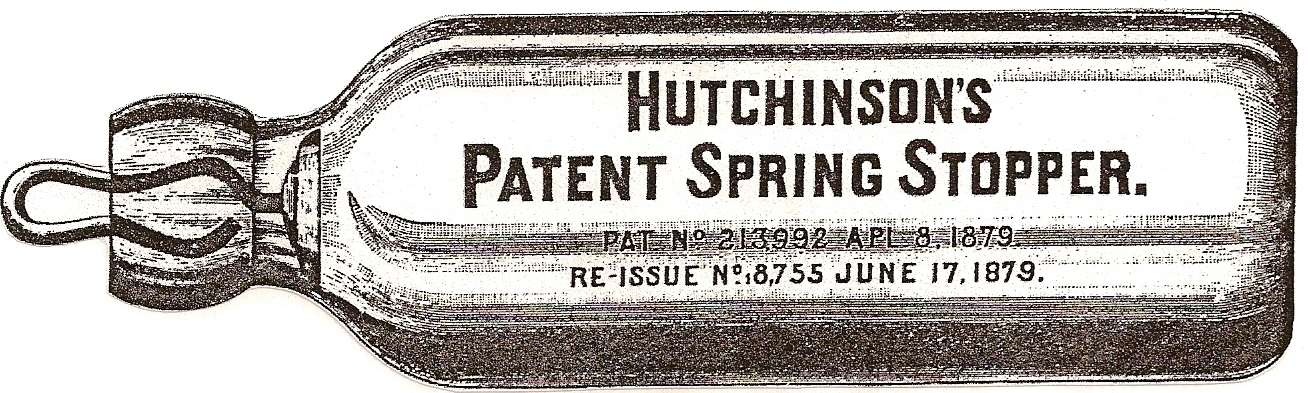

The 1889

W. H. Hutchinson & Son Manufacturers and Dealers in Bottlers Supplies

catalog offered the following advice to bottlers concerning syrups,

flavors, and general cleanliness:

TAKE NOTICE.

1.

Never flavor Syrups when hot.

2.

Stir each ingredient as soon as put into the Syrup,

before adding another, and stir well.

3.

Follow directions explicitly, and then if you

require a stronger flavor, or anything different, add to suit yourselves

and the locality you are in.

4.

You

cannot mix your Syrups and flavors too much; the longer you

stir them the better; and be sure you

strain them well.

5.

Have the tubs and everything used in making Syrups

very clean. It would be well

to keep lime water on hand, and every two weeks at least, wash

thoroughly all the utensils used in connection with the Syrups.

This will prevent them from getting musty, and kill all animal

matter that may have accumulated…

6.

We would advise all

bottlers to use a weak solution of sal. Soda and water in washing their

bottles…After washing the bottles in this water, rinse with fresh water,

and your bottles will be bright and clean as a new silver dollar.

HutchBook.com

HutchBook.com